Mapping Systemic Injustice: A Strategic Inquiry into Canada's Indigenous Water Crisis

Systems Mapping

Stakeholder analysis

Visual mapping

Strategic intervention framing

OVERVIEW

This project was developed during my MDEI days at the University of Waterloo, where we were tasked with exploring complex systemic issues through system mapping techniques. Our focus was the Indigenous water crisis in Canada—a longstanding injustice rooted in colonial systems and policy neglect. Through in-depth research and collaborative systems mapping, we uncovered the interconnected barriers to clean water access and proposed strategic interventions for key stakeholders. The goal was to create a foundation for policy shifts, advocacy, and community-driven solutions.

ROLE

Multidisciplinary Strategist & Systems Thinker

TEAM

Hanan K., Samaia A., Nicole G., Shannon C., Erica C., & Megan D

TIMELINE

4 Weeks

Why This Project Matters

My team and I started this project with a simple question:

How can a country with 20% of the world’s freshwater fail to provide safe drinking water to Indigenous communities?

What we uncovered was not a crisis of infrastructure alone—but one of history, governance, and ongoing colonial neglect. This wasn’t just a design problem. It was a systems problem.

At the time of this research, over 600 Indigenous communities in Canada were at risk, with 27 living under long-term drinking water advisories. Behind those numbers were: families boiling water daily, children getting sick, and generations grappling with the erosion of trust in institutions meant to protect them.

Zooming Out: Understanding the System

Our first instinct wasn’t to design a solution—but to slow down and understand the system. We approached this project as a strategic inquiry, mapping the invisible architecture that keeps this crisis in motion.

This included conducting an extensive literature review on government reports, Indigenous-led research, legal documents like the Indian Act—and used that to build a comprehensive systems map.

What emerged:

Colonial displacement forced Indigenous communities onto remote, under-resourced lands.

Jurisdictional confusion between federal, provincial, and band governments created gaps where no one was truly accountable.

Underfunding and misallocation of infrastructure dollars led to recurring failures, boiling-water advisories, and community-wide trauma.

And above it all, deep mistrust—fueled by decades of broken promises.

Key Insights

This project wasn’t about blaming one policy or department—it was about understanding how these systems reinforce each other, often invisibly:

The Indian Act still limits Indigenous control over land and water.

Short-term federal funding cycles often lead to quick fixes rather than long-term infrastructure planning.

Pollution from nearby industries—such as mining, fracking, and agriculture—often goes unchecked, directly contaminating water sources.

The result? A web of neglect that touches everything from physical health to spiritual practices, feeding into cycles of intergenerational harm.

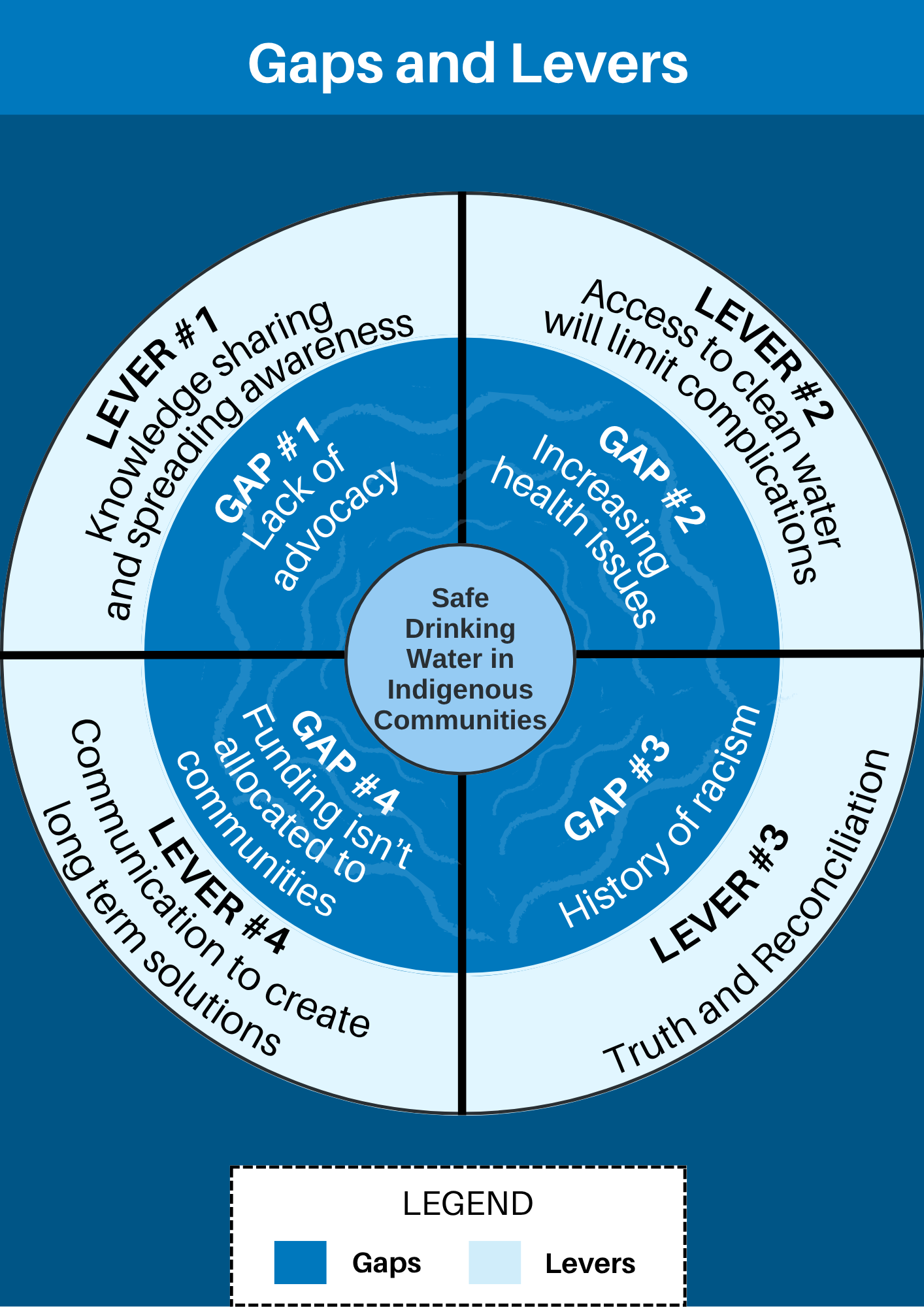

Leverage Points for Change

Within this web, I identified key points of leverage—places where intervention could meaningfully disrupt the cycle:

Indigenous Self-Governance

Support communities in managing their own water systems based on traditional knowledge, values, and needs.

Sustainable, Equitable Funding

Move away from temporary band-aids and toward community-led, long-term investment models.

Truth + Policy Reconciliation

Co-create water policy with Indigenous leaders. Not as stakeholders, but as sovereign nations with the right to lead.

Reflections & What I Took Away

This project deepened my understanding of how complex, interlocking systems—like colonial governance, environmental degradation, and economic marginalization—can reinforce and sustain structural inequities over time. The Indigenous water crisis is not the result of a single policy failure or technical gap, but the outcome of overlapping, deeply rooted systems that interact in unpredictable and often harmful ways.

One of the clearest takeaways was the critical importance of meaningful stakeholder engagement. Many past solutions have failed not because they were poorly intentioned, but because they were developed without real consultation with the communities most impacted. When Indigenous voices are not centered, proposed interventions tend to miss the mark—or worse, create new problems.

This project reminded me that research and systems mapping are not neutral exercises—they shape how we understand a problem and who we design for. It became clear that even the best-designed solutions can fall short without a deep commitment to equity, long-term thinking, and community-led processes.

If I were to continue this work, I’d want to understand more precisely where existing solutions broke down—whether due to jurisdictional confusion, underfunding, or inadequate consultation. And ideally, I’d want to speak directly with those impacted by the crisis, to better understand the lived realities behind the data, and what respectful and effective consultation would look like moving forward.

This project didn’t just expand my toolkit as a systems thinker—it sharpened my understanding of what it means to approach strategic work with humility, accountability, and a deeper respect for the complexity of lived experience